The Nearest thing to Heaven

Sheila Patrick, Kenneth Macleod and Dick Yorke, 3rd, 2nd and 1st from right respectively. Kenneth and Dick were RN officers from HMS Queenborough, who crewed for Sheila Patrick and Captain John Illingworth in Sydney in late 1945. Information thanks to Rod Macleod, Kenneth’s son.

Charlie Salter started it. His digging and research uncovered the story of Sheila Patrick. And then you, our Readers, continued it. Bob Chapman shared links and research. John Fairfax and Peter Costolloe opened boxes of Seacraft Editions and Emily Mackintosh, Sheila’s daughter, got in contact to share incredible stories. Find me one other person who can name Sir Francis Chichester and adventurer David Lewis as house guests?!

Sir Francis was to be re-named ‘Moley’ - for his love of messing about in boats - by Emily and her brother. and, Emily recalls, Sheila telling David to ‘bugger off’ when he requested she loan him her Folkboat for his Antarctic foray.

Emily also shared a chapter from a book HOLD YOUR COURSE by Susan Ingham an exploration of the way women entered the masculine world of mastering wind and water. Ingham has dedicated a chapter to Sheila’s story and it is with her permission that I am delighted to share it with SWS Readers.

The piece captures and conveys Sheila’s passion of her beloved harbour and being out on it. She lived for sailing and writing. She was a woman who in the 1950’s could leave small children behind to head up the coast on SVALAN, her Tum, for a bit of adventure. Emily recalls learning to sail by being tied to the mast with a piece of rope. It was indeed another time.

For my own efforts to encourage more women to sail, 70 years later, I feel I am living a parallel existence to Sheila. And while this warms my heart and I look forward to the day when I can offer myself as crew on Sheila’s now Melbourne based, soon to be restored SVALAN, I am frustrated by why social change is not only slow, but also thin. I feel we’ve let Sheila down in her push for greater diversity.

Susan - thank you for allowing us to share your words and on publication, I look forward to being able to update links to where we can purchase your wonderful book.

With great thanks,

Sal Balharrie, Editor

Sheila Elizabeth Patrick

Born 1917, D. 4 Jan 1995

From HOLD YOUR COURSE by Susan Ingham

Sheila loved the sea and had a life-long passion for sailing. She said that both her father and uncle were great sailors, they had yachts and lived by the water at Kirribilli and Cremorne where Sheila also spent most of her life.

In an interview she gave in 1980 when Sheila was in her 60s, she said of sailing, “I have always been a bit eccentric and done my own thing. My mother thought it would ruin my skin and make me unladylike, which it did, and I wasn’t encouraged. So that for me was a great challenge, I did it in spite of everybody.”

Her uncle, Les Patrick, was a professional skipper at the Royal Sydney Yacht Squadron (RSYS), famed for helming the yacht Bona to many victories. Sheila was an athletic and agile teenager in the early 1930s and Les took her under his wing, teaching her to sail.

Her first boat, MISTRAL, with a boys’ crew, won four races in the first seven weeks of the 1937 North Shore Dinghy Club and her second boat was a 12ft dinghy called VELELE, Polynesian for ‘dancing water’. The report of her win in a Vaucluse Regatta in 1939 read, ‘The girl skipper, Miss S. Patrick, had another win, piloting the North Shore dinghy, MISTRAL, to victory. Against the hard sou’-wester this young woman displayed rare cleverness.’

As a young teenager, she hung around a boat shed in Mosman Bay and made herself useful and, although she was ‘treated a bit rough,’ she said that in no time she was ‘out there sailing.’ As the article mentioned, Sheila had both male and female crew. Once, with the girl crew, they capsized right on the starting line and “…. everyone went around us saying, ‘ha-ha, serves you right’. We were eventually dragged ashore by my uncle (Les Patrick) who was sitting on the veranda at the yacht squadron.” (RSYS) He filled them with rum (which they probably needed by then) and “…. we were all so drunk we couldn’t put the boat away”, she said, laughing.

‘Treated a bit rough’ was putting it mildly. On one occasion the boys wedged her dinghy up in a tree. In response she threw their lunches in the water when they weren’t looking and they floated away with the tide. “You had to fight back…or let all their bicycle tyres down. I used to do some vicious things, she said, laughing, ‘but I survived.’ The ‘old man at the boat shed’, was Malcolm Campbell, and, upset for her, got a couple of old boys with a block and tackle to get her dinghy down. ‘Malcolm always supported me so I used to turn the lighthouse on and off on Cremorne Point for him. At dawn and dusk, no matter wherever I was, I would say: ‘Oh my God, I’ve got to go, I’ve got to put the lighthouse on!” It was when it was gas and, apparently, he got paid.”

Sheila turned her hand to everything that needed to be done, her own repair work, painting, varnishing. “You get a bit older and sex would rear its ugly head but you would….make it clear you weren’t interested in that sort of thing, you only wanted to sail. After a while, girls would come down after the boys and I found that ruined the atmosphere completely - I wanted to be sailor rather than a girl.” Sheila took up competitive sailing around the age of 18 and when asked whether she was up against any sort of prejudice, she replied yes, but that she overcame it “…by being better than they are. You have to work very hard at it….if I was losing and a bit helpless, they adored me but if I you win they don’t like you.”

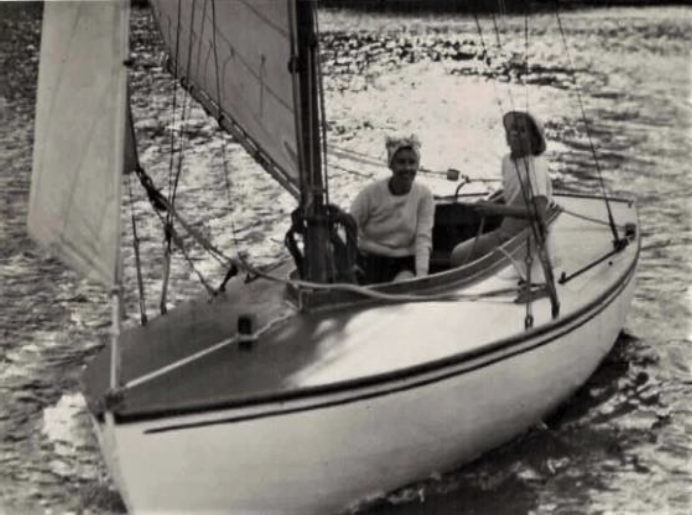

Sheila sailing her Jubilee.

The Daily Telegraph reported, “Miss Patrick has sailed 12ft dinghies for years against Sydney’s best male skippers, and this year has transferred to the Jubilee class boat.” Sheila said that my grandfather gave me £200 to go to university so I immediately bought a Jubilee.” She named it SOUTHWIND.

More than one sailor who raced with or against her said with grudging respect, ‘Sheila could hold her own’. John ‘Buster’ Brown, interviewed for his experiences for the Australian War Film Archive, was asked if there were many female sailors around when he was growing up and he said:

“ Not many. There was a girl called Sheila Patrick…. She was one of the first girls…. she tried to push me over the starting line, one of these things, you know, and I went crook at her but anyway, once again up at Port Watson’s Bay, we were both doing the same thing, having a go at one another, and we’d say “come on, cut it out Sheila, it’s Buster”. She said “you can still go to buggery”. She was a good lady.”

Sheila matriculated from North Sydney Girls High and began an Arts / Law degree at Sydney University but after the breakdown of her parents’ marriage, she had to give study away. Her father deserted the family and her sister looked after their mother who was seriously unwell, while Sheila went to work. Sheila gained a position as a ‘cadet under woman’ on Smith’s Weekly with Betty Riddell and, as her daughter, Emily said, “Sheila got the journalist’s bug”; journalism becoming her other life-long passion.

This image is from the War Memorial archive - “Heave Ho - Back to earth from sailing, Squadron Officer Sheila Patrick of Cremorne Point, NSW, before getting back to her work as a WAAAF Administrative Officer, Bowen, Qld, 5 June 1944.”

With the coming of World War 11 Sheila put the Jubilee away for 4 years went into the armed forces. She tried to join the Navy but at that time they weren’t recruiting women, so Sheila completed the Yacht Master’s Certificate to try to get a commission. The history of the Cruising Yacht Club of Australia (CYCA) records that “In 1941 she became the first women in Australia to obtain her Yacht Master’s Certificate”, but although the navy called her up, when they discovered she was female, that too fell through.

She then trained to get her pilot’s licence but “when I said I wanted to be a pilot, they just burst out laughing.” She eventually joined as a WAAAF8 and was stationed at Lake Boga, near Swan Hill, Victoria, at Australia’s secret No.1. Catalina Flying Boat Repair Base. She considered herself very fortunate because with each of her RAAF postings, there was water for her to sail her little VJ called SPRITE. Dinghies had been delivered to Lake Boga from the RAAF at Point Cook so Sheila, as the Marine Section Officer, asked permission to teach the girls from her section to sail as a recreational activity. “I was very bossy - you must have realised that by now – and I took over and really smartened them up.” Sheila’s sail training exploits were reported as follows: “… close contact in the confines of a sailing dinghy was a not an unwelcome duty. On occasions the girls had to be “rescued” by the Marine Section Boats because of dust storms or heavy westerlies.”

From Lake Boga, Sheila was posted to the Catalina Flying Boat Base at Bowen in Queensland, again on the water, and was flown up in a Catalina with her bicycle, dog and the VJ.

“We used to sail out from Bowen. I taught the other WAAAF officer to sail too - she was petrified in the beginning. We used to sail 7 miles out to Gloucester Island, sleep on the island and sail back. It was great - usually without our clothes - there was no one around, except the sharks. The VJ had about 3 inches of freeboard and the sharks used to go whistling by.”

After the war Sheila returned to journalism and in 1946, she established Seacraft magazine with Norman Hudson, of Hudson Timbers who provided the seed money. She worked at the Daily Sun as a newspaper reporter during the day and on Seacraft after work at night. Although Sheila never sailed the Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race, the first of which was held the previous year in 1945 with John Illingworth’s RANI the winner, she reported on the races. Sheila preferred being the skipper of the boats she was on. She said, “I haven’t been on a Hobart. I’m a skipper, and that’s it. Quite like crewing but I like to plan all things and have everything right…. I used to fly down for years for the fun and cover the Hobart race.” Sheila was a correspondent for other papers, including Daily Telegraph and she had her own page in the Woman’s Weekly. She found that being a journalist was a powerful position, although at public events she could be subject to verbal criticism for her reporting.

Throughout her life, Sheila made her own Christmas cards. This card is dated 1940-41.

In 1950 Sheila married Tony Cohen who she had met sailing and they had two children, Emily and Geoffrey. Tony curtailed his own sailing to run a furniture business and Sheila continued working, retaining her maiden name. Her daughter said that Tony resented her independence and didn’t want children and they divorced after 21 years, Tony having left the marriage.

All of this was hard on Sheila but Emily said, “Sheila was amazing, she raised us and inculcated her values in us: always to give things a crack and live with results, learn by your failures.”

Before she met Tony, Sheila had purchased a steep block of land down to the water facing due east at 180 Kurraba Rd, Neutral Bay. After the submarines entered Sydney during the war, people wanted to move west and waterfront land was relatively cheap. In 1966-7 they built a very modern house which was called Easterly, and it had a slipway. Emily and her brother grew up as waterfront kids: they lived in and around boats in bare feet and sailed - they had to, Emily said – with an unsinkable dinghy called PERIWINKLE. When sailing with Sheila, they wore coloured life jackets and Sheila tied the children to the mast so they wouldn’t go overboard.

In 1964 Sheila, a consummate navigator, joined the Australian Institute of Navigation as their technical secretary, a position she held for 35 years, as well as being Editor of their Journal. She became the fourth member to receive the Institute’s Award of Merit and she was eventually granted Honorary Life Membership.

Sheila continued sailing and racing throughout her life. She was athletic but not physically strong, so she sailed within her limits and the innovations in equipment, such as winches instead of a block and tackle, made boat handling for women like her much easier. In 1949, after saving up, she had a Scandinavian Tumlaren class racing yacht built in Tuncurry, NSW, by Alf Johansen, a well-known boat builder. She named it SVALAN, Swedish for swallow. The Tumlaren design was light and fast for its size and although small at 8.3 metres long, it carried a modest sail that was easily handled. Sheila Patrick successfully raced SVALAN with one of the first all female crew: she said,

“I used to have a crew of boys but I thought I would give the girls a chance. I can’t understand why most girls don’t take it up”.

Always adventurous, in 1956 she also sailed SVALAN to Port Stephens with a friend. She recounted the experience for the August edition Seacraft magazine in an article titled, “Two’s Company,” and wrote, “Cruising in a Tum might be OK on the Hawkesbury, but two girls, cruising the open sea, alone - well...” That story is published in the edition of SWS - see Sheila’s Sea-going-Craft.

Sheila sold SVALAN in the early 1970s, but continued sailing a Folkboat she had built by Hald & Johansen which she called CAPELLA of KURRABA. Among the stories of her sailing, there was also a Kavieng outrigger canoe that she acquired when in Papua New Guinea. She sailed it around Shell Cove, “out of control, of course,” Emily said. Sheila raced with a number of clubs including the Royal Prince Alfred Yacht Club, and the Royal Sydney Yacht Squadron but it was the Royal Prince Edwards Yacht Club on Point Piper that was the only yacht club to grant Sheila full membership at a time when women could only be Associates and were not recognised unless boat owning skippers.

Speaking of sailing in the 1960s, Sheila said, “It’s a daft kind of recreation….I think we were all fairly eccentric. It wasn’t really fashionable. Yachting has only become fashionable lately, the last 20 years or so.”

In 1949 she became the first female member of the Cruising Yacht Club of Australia. In 2001, fifty-two years later, in recognition of her achievements in sailing and in the growing appreciation of women in sailing generally, the Associates Committee of the CYCA created the Sheila Patrick Memorial Trophy for women who have completed the Sydney to Hobart yacht race at least 10 times. As the numbers of female sailors increased, the Associates Committee of the CYCA also recognised women who have sailed more than 15 Sydney to Hobart races with a separate trophy, the “Associates Perpetual Trophy”. Adrienne Cahalan received this trophy in 2006 and, as of 2020, had completed 28 Hobarts.

Sheila lived at Easterly, overlooking

Shell Cove all her life and was known as the Harbourmaster of Shell Cove.

She declared that they made her Harbourmaster because she was always complaining about what went on in the bay, so the Harbourmaster of Sydney said,

“I’ll give you a hat and a flag and shut up, you’re now the Harbourmaster of Shell Cove and you’re responsible for it.” Sheila continued, “That entails keeping it clean and tidy and if anyone comes into Shell Cove, they should ask me – they don’t always ask me but I’m in charge – and the Maritime Services Board know it too. I have a flag with MSB device on it. I must say the hat doesn’t fit me; I’ve got a very big head.”

Sheila made life-long friends and had a range of interests. Sailing friendships included Bobby Miller, the sailmaker and yacht designer associated with the America’s Cup win who changed his name to Ben Lexcen, and John Illingworth who she called the best sailor she ever met. Fellow journos from ABC, such as Paul Lockyer, Tim Blue and Geoff Leech crewed for her and she mentored the champion sailor, Vanessa Dudley. Sheila was not a very good cook, hated house work and most things domestic but was well-read, loved art and went to concerts.

“You could talk to her on any subject and come away knowing you have just had a discussion with a well read, informed and intelligent women,” Emily said.

Sheila was a chronic asthmatic all her life and the medication reduced her bone density and made her fragile. She was determined to spend her last gasp at Easterly with its view, and she did.

In her interview she commented:

“To me the greatest joy is to go down to the Harbour and sail in a little boat in a nor’easter on the wind in the morning when there is no one about and it’s just gorgeous and you’re sailing along – it’s the nearest thing to heaven.”

We look forward to publishing details of

HOLD YOUR COURSE