The uncontrolled enthusiasm of paddling canoeists to hoist a sail or two

Sincere Thanks to Steve Burnham for allowing us to publish this article from his engrossing website

The Elwood Seahorse

The Seahorse, an Australian designed sailing canoe, was developed in the early 1930s.

The one design class possibly originated as a response to the uncontrolled enthusiasm of some paddling canoeists of the day to hoist a sail or two for the odd impromptu bumping race on Port Phillip Bay.

The first Seahorse was built in Melbourne’s bayside suburb of Elwood in 1934 and was put in the water in November of that year for trials. After finding no flaws in the design, it was finally declared ready for the public and in the following year five more boats were built.

The Elwood Sailing Club specifications for the class, dating from this era, says that the class ‘originated from the belief that a small inexpensive yacht could be developed to serve both as a safe comfortable sailing craft for cruising and as a responsive, lively racer’. It seems that the design was actually developed at the Elwood club as an evolution to various hybrid canoes that had been sailing from this beach for years.

The Elwood club was originally a paddling canoe organisation, and the early adaptations to sail were seemingly put together as each individual owner saw fit. By 1939, 22 Seahorses had been completed, and all but one constructed by amateur builders. During the next six years only one boat was built owing to the war years and the policy of the club not to use materials, but 1946 saw the class again going ahead and at the end of that year 10 sets of plans had been sold.

The specifications introduction goes on to say: ‘It was determined by experienced members of the Elwood Sailing Club that the required boat would be 18ft long with 4ft beam and watertight bulkheads fore and aft to enable it to be righted if capsized. From this evolved the well-known Seahorse One Design Class.’

Ted Montfort, president of the Seahorse Association and one-time Commodore of the Royal Melbourne Yacht Squadron, says that at present there are still about 100 names on his list of members, and that about 30 odd usually turn up at the yearly meetings he chairs. Ted knows of only two Seahorses in existence, but supposes there are more that no-one knows about. ‘They could be fairly wet boats,’ says Ted, ‘but some of them had a splashboard running on angles up to just forward of the mast. This would throw back a bit of the water when you were punching into any sea.’

However, some of these ‘splashboards’ were little more than canvas arrangements propped up with sticks and made so they could be lowered when not needed. They were perhaps a carry-over from an earlier ‘lee-cloth’ arrangement found on some of the very early sailing canoes of the area.

Life jackets were not really the norm in those days. Ted says that one of the requirements the Elwood club had was that sailors must prove that they could swim, fully clothed in their sailing gear, from the club to a diving platform off the beach and back again. ‘Also, every year before you could start,’ says Ted, ‘you had to take a ‘bottling test’. The boat would be put in the water, with the mast up, and tipped over for three minutes on each side and then upright for five minutes. If after that time there was more than three inches of water in the bottom of the boat you were not allowed to sail.’

Two box-like pumps were usually fitted on either side of the centrecase, the valve inside worked by a piece of leather thong from the top. The water was let out directly into the case, and there was also a bung into one side of the case for draining the boat when on the beach.

The rig was high peaked gunter, with a jib set to the stem. The total area for the working sails equalled 144 sq ft, with the spinnaker adding another 85 sq ft. Interestingly, silk or nylon was barred from the class as a sail material, and a loose footed or mitre cut main was not allowed.

Inside ballast and winches for halyards were also prohibited, as was ‘any apparatus extending outboard which may be to support or assist in supporting a member of the crew outboard’.

The hulls were lightly planked and the entire thing covered with 10 ounce canvas, which was held on mostly with paint but was also tacked on all along the gunwales. Red lead paint was worked into the canvas before undercoating and finishing off. ‘The canvas would have to be repaired every so often,’ says Ted, ‘or worse still would have to be entirely replaced. You may find a rock or shell just under the sand which could put a tear in the canvas. You could always re-stick it back with paint, or make a patch, but one could re-canvas the lot anyway. But this was a big job. The outside keel would have to be removed, and the rubbing strakes and some fittings.’

Planking was an easier than usual process, and must have suited the backyard builders that seemingly made most of the boats of this class. After moulds and ribbands were set up, the keel, stem and stern pieces and the ‘inside gunwales’ (as the specifications say) were all fastened to the mould. Then the ribs (quarter inch by two inches, at five inch centres) were steamed and fastened to the gunwales and keelson, but were set flush into the outside face of the keel. To make things even easier, it was also specified that ribs were to be fitted in two halves, that is joined in the centre of the keel, and not bent around the hull in one piece. Planking was therefore not rabbetted into the keel, but went over the top of the lot.

The ‘gunwale planks’ went on first followed by the single ‘garboard’ strake, which was screwed to the keel and stem and stern pieces as well as being riveted to ribs. Planks were then fitted next to the gunwale and garboard strakes alternately until closing the hull with the last plank on the bilges, which from the shape of the gap created by the other planks would be short and pointed at each end. A gap for swelling was left between the planks, usually measured by placing a hack saw blade between them when fitting.

One trick for helping fit the plank over the curve of the hull at the bilges was to soak hot water on the outside of the plank with rags. This swelled the fibres of the wood on the outside and helped bend it in towards the curved ribs. After being sealed up with the canvas, an outside keel was fitted along the bottom and any other pieces and fittings needed could be attached.

Ted Montfort says that in the Seahorses’, and his own, heyday, they often sailed down Port Phillip Bay to the Mornington Peninsula, or over to the other side, for a bit of a holiday.

‘No one had trailers anyway, so sailing them was the only way to get them anywhere. In those days you could leave all your gear on the beach and no-one would touch it.’ The natural elements were another thing. ‘One time after a night at Sorrento, we woke up to find two of our boats gone,’ says Ted. ‘Either the tide rose higher than expected or we didn’t do the right thing when coming up onto the beach.

Anyway, it seems a local fisherman found them drifting out on the bay and took them in tow. The only thing was, he didn’t know from looking at them just how tender they could be. So when he tried stepping onto one, he got a soaking. ‘We didn’t know all this at the time. The boats were tied up to the jetty at Sorrento, and the proprietor of the shop that was on the jetty in those days told us all about it. Since the fellow that towed our boats back wasn’t about, he suggested we could perhaps pay for his tobacco, so we all put in. That was the least we could do.’

So what was the fate of the Seahorse, and why has this class of boat all but disappeared? The generally held opinion seems to be that with the advent of newer materials and building methods, the design simply fell out of favour with the owner-builders that seemed to make up most if not all the Seahorse’s advocates. And yet, as a unique Australian development, the design certainly deserves its place in history. Indeed, given its simplicity and seemingly satisfactory performance, we may even see something of a renewed interest.

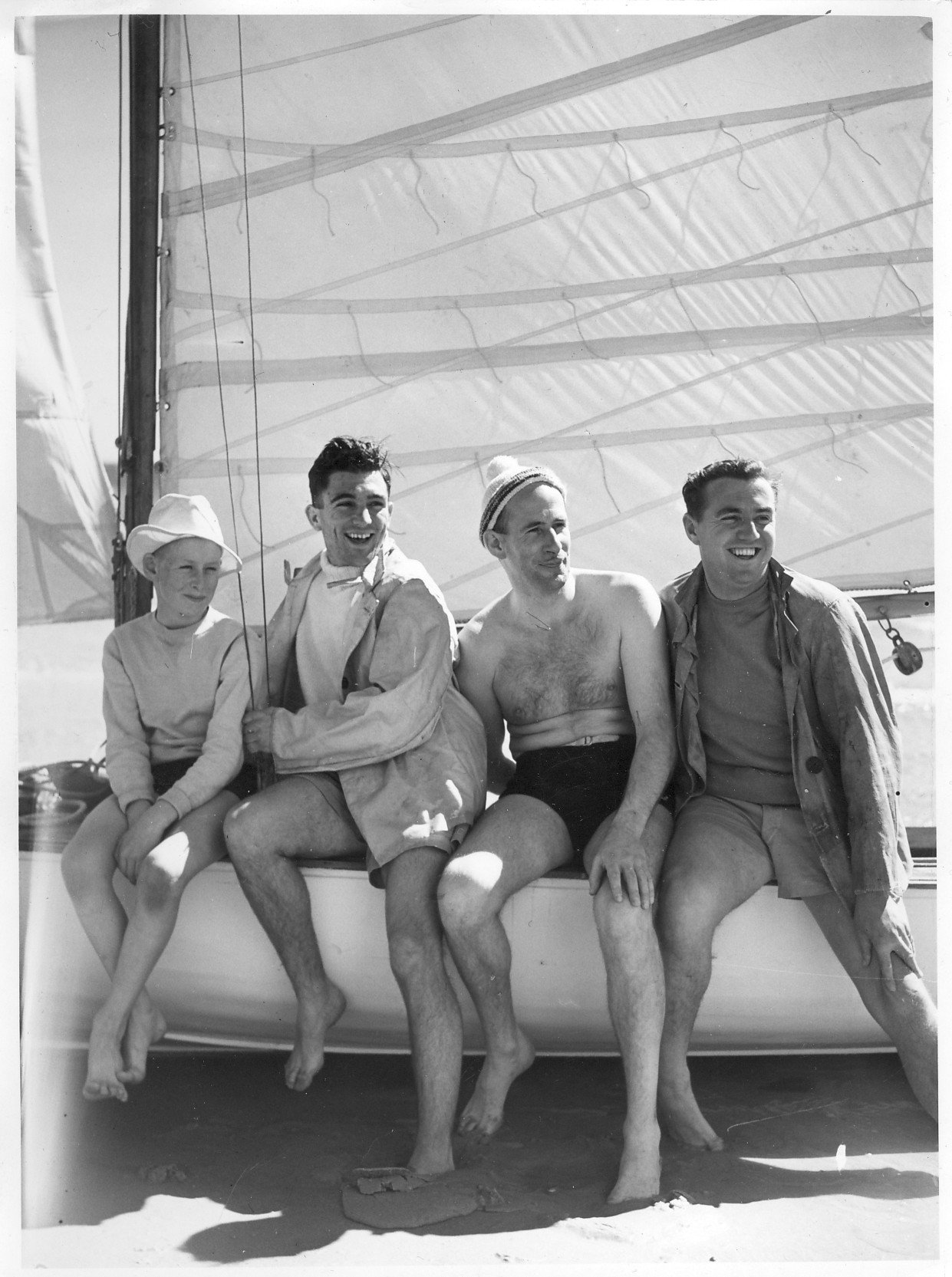

Evolution at work: pre-Seahorse canoes

Bill Richards, long time local of the area, remembers the earlier sailing canoes that were raced off the beach around Elwood before the Seahorse design was established. The Elwood Yacht Club was originally a paddling canoe organisation, and by the 1930s had established a large storage shed on the beach with racks for canoes up to three high. The canoes, says Bill, were of various shapes and designs but mainly 16 to 18 feet long.

‘Canadian built 18 foot Peterborough canoes were the Rolls Royce of the type,’ he says, ‘although the Canadian influence was apparent in most canoes of the time’. Hardly any young person had a car in the 30s, so transport of the canoes was out of the question, hence the beach storage facility. ‘They were very lightly carvel planked with tiny ribs, perhaps a half inch by one quarter inch,’ says Bill. ‘The better ones were varnished inside and out, but some were only stretched canvas over ribs and stringers.’

The sailing adaptions of some of the canoes were at the whim and fancy of the owner. ‘In some cases the rig was ketch or yawl, which was easily done because the rudder could be connected, as was carried over to the early Seahorses, by cords. The cut of the main was called ‘bat-wing’,that is, fully battened and with a greatly exaggerated rounded leech – the idea being to get the maximum sail area from a short mast. For the same reason the ketch/yawl arrangement was often encountered.’

‘Stability is a factor in which these canoes did not excel, and with the earlier types, before the regulated Seahorse design, there were no flotation bulkheads and no way they could be righted in any sort of sea. It was a day to remember that was free of any sort of capsize – called ‘bottling’.’

The earlier canoes were originally built with a high priority for lightness, the keel was accordingly very light, maybe two inches by one inch, and therefore unsuitable for a plate case. So lee boards were the standard of the day. Lee ‘clothes’ were another part of the effort to keep the canoes afloat. ‘These consisted of strips of canvas about eight inches wide running around more or less upright, but tending inboard, on each side of the canoe and fastened to the gunwale,’ says Bill.

‘The lee clothes were held up on the leeward side with spaced vertical timbers attached to the inboard side of the cloth. The idea was to have a propped up cloth on the lee side of the canoe, but an unpropped one on the weather side so the crew could still sit on the gunwale.

More stories by Steve Burnham on Classic Boats, Wine and cycling can be found on his website

See comments!