A Death Defying Voyage of Pleasure

Painting of the PACIFIC by Andrew Murray

This week we publish the first in a series of stories from a book by Russell Kenery called “Curious Voyages”. Its a collection that was never meant to be a history of sail; just a voyage through curious sailing adventures that reflect the truism that truth can be stranger than fiction. I can’t believe that I had never heard the story of Bernard Gilboy and his tiny PACIFIC, a story that was so nearly connected with Australia.

Lone sailor Bernard Gilboy’s small boat voyage, in 1882, was perhaps the most daring undertaking on the world’s biggest ocean. Yet, when departing San Francisco, the Customs Certificate read, “starts on a voyage of pleasure for Australia.”

The Queensland schooner ALFRED VITTERY was northeast of today’s Fraser Island when it encountered a badly weathered 18ft boat. The schooner positioned alongside, and a deck-hand threw a line across its bow. Onboard the tiny craft was an emaciated sailor so debilitated he could barely crawl forward to take a turn with the line, but he did. When asked where he was from, the exhausted sailor, Bernard Gilboy, replied, “San Francisco, 162 days”. The schooner’s crew were sceptical, but Gilboy had indeed sailed his small boat 7,000NM from California and, when rescued, was only 160NM short of his destination: Australia.

Bernard Gilboy grew up in Buffalo, New York, and always had a preoccupation with the sea. As a 17-year-old, he enlisted in the Navy, served for three years, eventually moving to San Francisco near the Pacific Ocean. Years later, the San Francisco Examiner [19 August 1882] reported that he had “considerable experience in sailing small boats and had been once fifty days at sea in an open boat.” That was a 2,000NM passage, from British Columbia to the Sandwich Islands, in a small Columbia River Salmon Boat designed for use in the powerful estuary of the Columbia River.

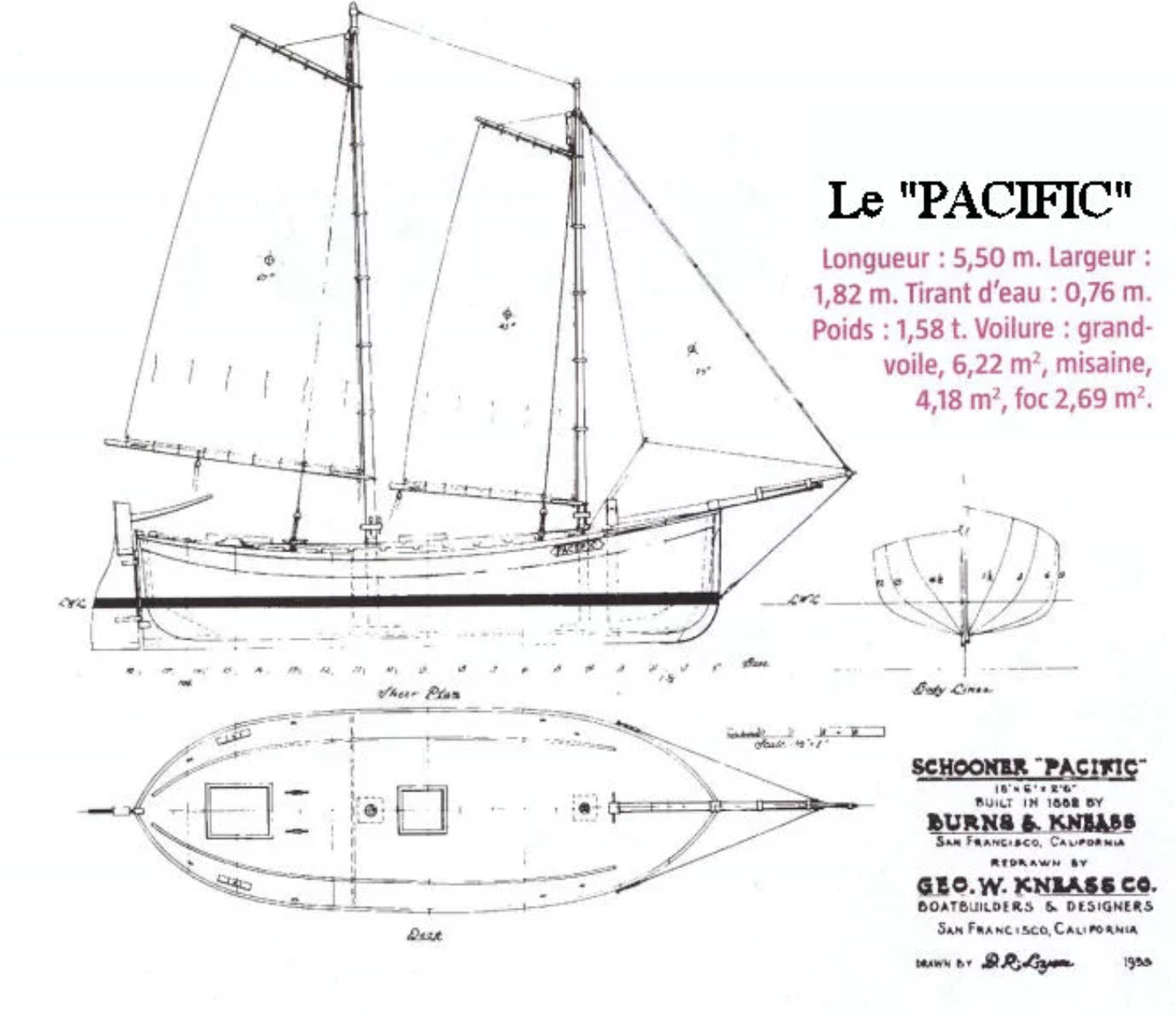

As a lone sailor, Gilboy was inspired by Alfred Johnson, who made the first recorded single-handed trans-Atlantic crossing from Massachusetts to Wales, 3,000NM in a 20ft dory. Gilboy commissioned San Francisco boatbuilders Burns & Kneass to build him an 18ft boat named PACIFIC. Because the prevailing easterly winds on a California to Australia passage make it a ‘downhill’ run, the yacht designer, Richard Lyon, was asked for a boat that would sail well off-the-wind rather than point high into it. Lyon designed a sturdy 18ft double-ender, the hull fuller aft than forward, with a 6ft beam based on the three beams to length hull-ratio for good carrying power and seaworthiness. Construction was carvel-planked in cedar on white oak frames, with spruce deck and spares. The timber deck was also covered in canvas, with a hatch amidships and another aft. Gilboy chose a schooner-rig, having the foremast shorter than the mainmast. His thinking was that having two masts, “if one mast went by the board mid-ocean the remaining mast may not”, and with that in mind, the masts were unusually designed to be readily removable. The rig also had a bowsprit-mounted headsail. For trimming purposes, the forepeak stored 140 gallons of water in casks, and when each was drunk, he refilled it with saltwater. When fully loaded with five months of provisions, PACIFIC sat very low in the water with precious little room for Gilboy himself.

The only exiting photograph of the PACIFIC

Few knew of Gilboy’s exploit, so when he departed on Friday 18 August 1882, the only fanfare was three-cheers from a few onlookers. A couple of days later, on 20 August, the newspaper San Francisco Call report reported, “All aboard for Australia!” shouted a man Friday morning as he drew out from the Washington Street pier in a small sloop. He passed on down the bay and out the Heads. Nothing is known along the water front of the mysterious stranger, nor have any clearance papers been issued to him out of the Customs House.”

The first night was spent anchored off Lime Point, inside San Francisco Bay, and Gilboy cooked his first meal on the kerosene stove. The following day, he sailed out in a fresh breeze into the open ocean. Being deeply laden and with a heavy beam sea, PACIFIC shipped waves on deck, otherwise handled the conditions well. Gilboy feared being run down by-passing ships, so his routine was to stay on watch all night, then he hove to at sunrise. To heave to Gilboy lowered both headsail and foresail, tied both tiller and mainsail amidships, and tossed overboard a 4ft x 6ft canvas sea anchor. The mainsail steadied her heading to windward while the drag kept Pacific’s bow to the sea, even in heavy weather. In the first weeks, Gilboy headed south to pick up the prevailing west wind but was frustrated for a month by headwinds and calms, and September drifted away.

In early October, the westerlies arrived and carried PACIFIC on course. When hove to Gilboy was often disturbed by knocks on the hull and found when schools of fish surrounded the boat, sharks would come alongside, turning over to gulp down as many fish as possible. On 4 November, the Pacific reached French Polynesia; Gilboy sighted the volcanic Marquesas Islands, then the Tuamotu Archipelago on 11 November. Ninety-three days into the voyage, Gilboy sighted the barquentine TROPIC BIRD, on passage from Tahiti to San Francisco, and rafted alongside. He was given not only correct longitude but also some provisions, including fresh fruit. PACIFIC continued running westward, on many occasions topped 100Nm in a 24-hour-period, and when becalmed, she was surrounded by giant sea turtles and schools of Bonita fish. She passed south of the Society Islands, and on 25 November, Gilboy took a landmark sight of Palmerston Island, a speck of a coral atoll in the Cook Islands.

On 13 December, south of the island Tonga-Tabu, PACIFIC was running in heavy weather with powerful rolling swells. Both mainsail and foresail were reefed, a large sea broke at its crest under the boat capsizing her, and Gilboy was tossed overboard. He grabbed hold of the drag-line and managed to clamber onto the upturned hull. It took almost an hour of hard hauling before he pulled PACIFIC upright but being full of water and unstable, she rolled over again. Gilboy laboriously righted her a second time, quickly cut the shrouds, and unshipped both masts. Gilboy tied them and their sails and spars onto the drag-line to help keep PACIFIC’s head to the heavy sea. As Gilboy bailed her out, he discovered both the compass and watch were lost. Navigation would now have to be by dead-reckoning, a guesstimate procedure with cumulative errors that would prolong the voyage, a major problem given most of the provisions had also been lost. The rudder was also gone, so Gilboy fashioned a steering oar by lashing a rowing oar to the spare boom. Then, when he hauled in the drag-line, he found the mainmast and mainsail had worked adrift and lost: his thinking was correct re two masts being better than one. He stepped the foremast, hoisted the foresail and headsail, and jury-rigged the three-cornered studding-sail. He hoisted its peak up the foremast, lashed its foot along an oar, and set that aft. The jury-rig’s lower center of effect made PACIFIC more stable, and she sailed well under it when the wind was abeam or when running before it, ‘gull winged’ out.

On 15 December, PACIFIC got underway again in a good, steady breeze, but late in the day, more drama came in the shape of a large swordfish. It shadowed PACIFIC then suddenly attacked, its sword spearing Pacific’s hull close to the keel. Gilboy plugged the hole from inside with a wooden wedge and lamp-wick. Although it leaked a little, the temporary repair remained for the rest of the voyage. Six days later, a large shark raised its head out of the water beside the boat, stared blankly at Gilboy, then swam off when he beat it with an oar. Provisions were critically low, and Australia was still 1,200NM away, so Gilboy headed for New Caledonia. As he closed on the island, high wind forced Gilboy to heave to, and for four days, PACIFIC was driven in a near-gale southwest, way out of position to reach New Caledonia.

On Christmas Day, Gilboy sighted Matthew Island, so he ran PACIFIC toward it in the hope of at least finding coconut trees. Instead, all he saw when closing the shore was barren volcanic rock and dangerous-looking reefs extending miles out to sea. He hauled PACIFIC up to windward and for two days and nights clawed north to try to clear the island. Eight miles offshore, the precious log was snagged on a jagged reef and lost. On the third day, an exhausted Gilboy fooled himself that the noise of waves was surf on a beach, but it was breakers on a reef. White water ahead stretched from the shore, past the boat, and out to sea as far as he could see. Gilboy had no option but to run PACIFIC over the reef, and although she almost capsized in the boiling breakers, she rode through to smooth water. Gilboy could hardly believe his luck and felt blessed when a flying fish flopped aboard as his dinner. After anchoring for two days to recuperate and fish, Gilboy continued running PACIFIC westward. For the next four weeks, Gilboy was slowly starving to death, and he eventually let PACIFIC head by the wind and steer herself.

Gilboy before and after the voyage during which he lost 13 kgs

By 29 January, Gilboy was only semi-comatose, slumped in the stern, hardly able to move, but his eye caught sight of something small and white to leeward. His imagination saw it like a sail, and although hardly believing his own eyes, he squared before the breeze to try and cross it. Barnacles on Pacific’s hull made her painfully slow, so Gilboy tried waving his umbrella, but it slipped overboard from his feeble grip. The same happened with a flag. Gilboy now made out it was indeed a schooner, and in desperation, fired his revolver until empty. It slowly turned toward him. It was the ALFRED VITTERY.

Russell Kenery lives on the Mornington Peninsula, he’s a yachtsman, an enthusiast for the heritage of boats, and author of ‘Matthew Flinders-Open Boat Voyages,’ and ‘Curious Voyages,’ an illustrated collection of true sailing tales.

The watercolour painting and pen-sketch of PACIFIC is by Andrew Murray, an illustrator with a lifelong love of maritime art & the sea.