Dinghy Democracy

De Havilland Comet Racer in original livery

It’s been hard to write about timber dinghies while live-streaming the sailing regatta from Tokyo 2020. There’s not much romance in plastic boats but that’s made-up with strict one-design rules ensuring sailing skill wins the day.

This is the third story about the development of small boat sailing in Australia and New Zealand. See SAIL BAIL or SWIM (SWS 24th June) and TAURANGA P CLASS (SWS 8th July).

We can all name our favourite ply chine or ply moulded dinghies like the Sabot, Tauranga P, International Cadet, Cherub, Fireball, Finn, Flying Dutchman, Gwen 12, Mirror, Moth, Rainbow and VeeJay. In the 1950’s and 60’s, off-the-beach sailing became an affordable family activity with huge interest in these new boats. Lightweight inexpensive dinghy classes for kids and teenagers were on drawing boards or being developed in boatbuilder’s sheds while beachside sailing clubs were starting up all over Australia.

This was only made possible by technical developments with ply sheet, moulded timber fabrication and resin glues used by aircraft in the 1930’s. The necessity of industrial scale production in the following wartime years, refined these materials and methods. SWS will pick out a few stories and you can do the rest.

FLY with PLY

Centenary Air Race Poster

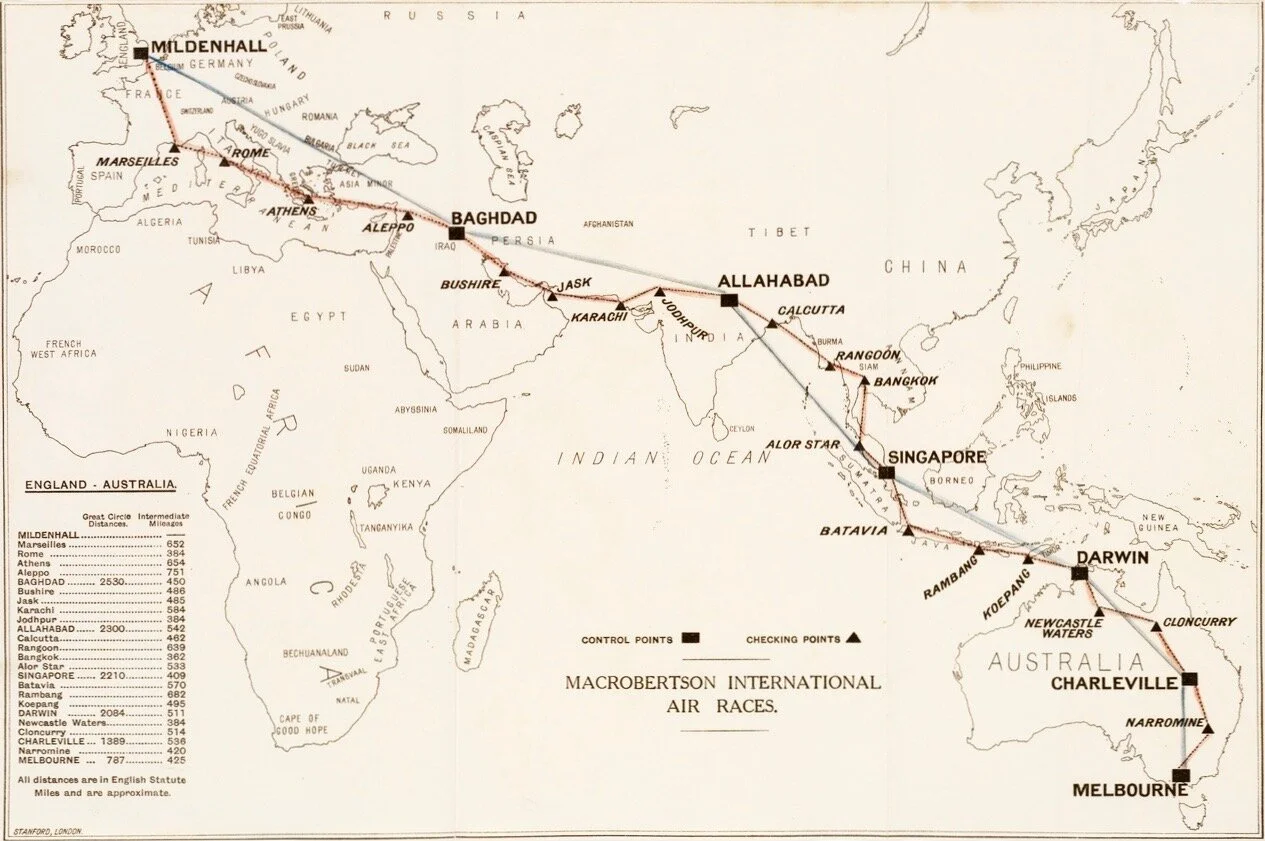

The De Havilland Aircraft Company in England designed the DH.88 Comet Racer as a high-speed, twin-engine, two-seater to compete in the 1934 air race from England to Australia. The race was sponsored by the Melbourne philanthropist MacPherson Robertson of the famous confectionary company to celebrate Victoria’s Centenary. More important than his race sponsorship and a gift of the Herbarium in the Botanical Gardens and funding of Mawson’s second Antarctic expedition in 1930 was MacRobertson’s made the “Cherry Ripe” in Fitzroy and invented the “Freddo Frog” in 1930.

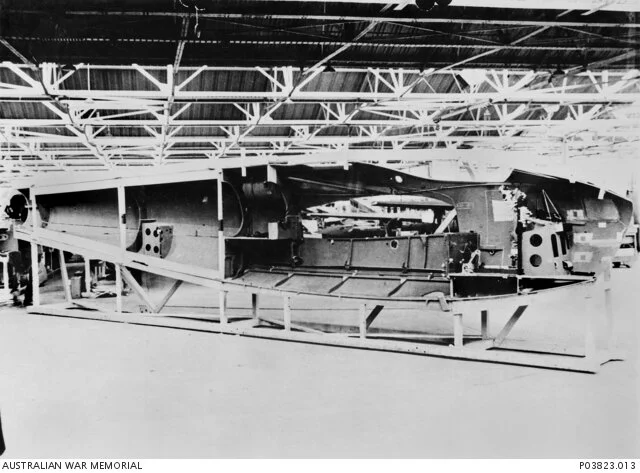

The development of the DHA Comet Racer pushed lightweight timber technology to its limits. The plane was made almost entirely of wooden components except for the engine bearings and undercarriage. The wing was birch ply box spars and spruce stringers through the length with the lateral ribs, shaping the wing curve also made from birch ply. The structure was laid with two skins of diagonal 2” wide spruce planks milled between 3.6mm to 13mm to suit location and stress loads. The fuselage was framed similarly and also used ply skins. The timber components were held together with recently developed high-strength bonding resins. Five planes were built and Comet G-ACSS “Grosvenor House” won the race in October 1934, landing at Flemington Race Course in under 71 hours.

Race ready Comets at RAF Mildenhall, Suffolk before take-off 1934

Centenary Air Race Map

WATERPROOF GLUE

Ply had many early problems when used in aircraft and boats. The ply would delaminate in both cold and tropical climates, especially when wet. Early de Havilland aircraft used birch ply veneer with balsa wood spacers and Casein, a liquid milk-based protein glue formulation. There were still problems with natural air gaps in the wood structure and between veneer layers. Penetration of moisture into these areas would freeze and thaw during flight breaking down the laminates. Only when a urea-formaldehyde glue called Aerolite was used under heat and pressure did the structure develop integrity and moisture resistance.

Goldman AG in Germany was working on similar technology and made a significant breakthrough with Tego film in 1930. This was a sheet of paper impregnated with phenolic resin and laid up dry between timber veneers. This technique avoided deformation often seen during application of liquid glues. When heated under pressure, air gaps were filled and the ply layers became unified, strong and waterproof. Knowing the Germans had a significant technology advantage with Tego film made Goldman AG a wartime bombing target and the factory was destroyed in 1943.

Classic sailors will be familiar with Tufnol blocks. These are made with layers of cloth soaked with phenolic resin and pressure cured with heat. Holland Yacht Equipment or HYE are still making “hard tissue” blocks and cleats in Monnickendam Netherlands.

Comet Racer restoration showing ply spars and ribs to make the single wing.

TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER

The allied war effort meant significant technology transfer from England to Australia. De Havilland setup in Melbourne in 1927 before moving to Sydney in 1930. From 1940, they were making Tiger Moth bi-planes, used as flight trainers by the RAAF. The Moths were assembled in the Bankstown factory from imported fuselages and locally made wings. This developed local knowledge and skills with ply and timber laminate construction. The famous twin-engine DH.98 Mosquito fighter-bomber, capable of speeds that left enemy planes behind, was also made in Bankstown and saw service with the RAAF during the Pacific war. This famous twin engine plane, born of the Comet Racer was mostly ply and laminate construction. The B&W picture below shows the method of making the ply fuselage in two halves.

De Havilland Mosquito at Fairbairn Air Base ACT 1946.

Mosquito ply fuselage during construction at De Havilland Bankstown NSW 1945

De Havilland continued as an aircraft manufacturer after the war building the first commercial jet airliner - the Comet. Their ply technology and fabrication systems left a lasting influence on Australian manufacturing and boat design. Another English aircraft company re-deployed its wartime timber technology to make boats and keep the company going after the war.

FAIRY MARINE

Fairy Aviation on the Hamble near Southampton had a large stock of birch ply left over in 1944, so they formed Fairy Marine to produce Uffa Fox’s design for a national 12ft dinghy. The yacht, named Firefly after their famous aeroplane, was built on jigs with strip ply laminates then cooked in a steam pressure autoclave large enough for Fairy’s aicraft wings and fuselages. This is hot moulding.

Charles Currey with early laminated Fairy Firefly on the Hamble River.

The race was on to develop dinghies for the 1948 London Olympics. Uffa Fox worked with Charles Currey, the Fairy Marine Sales Manager to design the Firefly. Currey was a naval architect and accomplished sailor. Getting a class included in the Olympics was a booster for any company to guarantee sales and international licensing. While the Firefly was designed as a two person dinghy, it was actually nominated as the single hander for London. Paul Elvstrom, the Danish representative won Firefly gold but by the 1952 Helsinki games, the Finn replaced the Fairy boat. Rickard Sarby, a Swede was the designer of this stay-less cat rigged boat. Elvstrom won gold in a Borresen Finn with Charles Currey taking silver in his Fairy Finn, after seeing-off challenges to his amateur status. Elvstrom, the master helmsman, won again in Melbourne 1956 and Rome 1960.

Great skill and strength was needed to sail and trim an early Finn. The photo of Elvstrom sailing in Helsinki in 1952 shows the original rig. The boom is simply wedged into the unsupported mast like a mortice and tenon. There’s no kicking-strap requiring all trimming and tension through the mainsheet. Elvstrom had plenty of time to study the problem and is credited with inventing the vang.

Uffa Fox in duffle coat with Charles Currey sailing the prototype Fairy Firefly.

Fireflys being allocated to helmsman by ballot. London Olympics Torquay 1948

Fairy continued collaborating with Uffa Fox to design the Fairy Swordfish and 18ft Jolly Boat hoping to be nominated as the two-handed dinghy at Helsinki. They were unsuccessful but the boats still became popular classes around the world. There’s a strong JB fleet still sailing at Port Melbourne YC. It took many years before the Flying Dutchman was selected for the Rome Olympics in 1960. Regardless Fairy Marine became a major producer of hot moulded boats like the Finn, Flying Dutchman, 5o5 and International 14. Their system introduced industrial scale ovens with controlled pressure to force the clamped forms and ply layers together while the heat cured the glue. This produced a light and very strong shell structure resistant to delamination. The same result can be achieved with quite low-tech vacuum cookers as we’ll see with Rob Legg in Melbourne from 1948.

Charles Currey helming a Fairy built International 14 in Bermuda.

ROB LEGG - AGAIN

The story of Rob Legg is at SAIL BAIL OR SWIM SWS 24th June. RL’s story is a homegrown version of Fairy Marine. His boat building skills combined with intelligent trial and error using crude equipment, finally produced beautiful ply laminated craft.

After the war, Legg joined with Bob Keeley, his 14 foot skipper as a sailmaker but with rationing of Egyptian cotton there was not enough material to keep them both busy. After building his own St Kilda 8 footers at home in Collingwood, Legg wanted to ride the demand for dinghies and declared himself a boatbuilder. He started out in his father’s chook shed in Somerville, near Stony Point on Western Port Bay by experimenting with 3 cross-laminates of 1/16th ply (about 1.5mm) glued and tacked over the carvel hull of a familiar 14 footer.

RL visited a furniture manufacturer who was using a vacuum pump to make curved veneer mouldings. To test the method he built a small 8ft dinghy and sealed it in a rubber bag connected to a surplus aircraft vacuum pump and electric motor. With only 8lb of pressure the jig frames and veneer laminates collapsed. RL’s intuitive solution was simple and followed the de Havilland technique. The hull was built in separate halves that did not distort under pressure. He made the form jig from cross veneers before laying up the hull with five cross laminates using linseed oil as the slip layer. The two finished halves could then be easily assembled with rebates left for the keel, stem and transom. Curing the glue proved a problem in Victoria’s wet cold winter. RL built a crude galvanised iron oven with a wood fire underneath to heat the vacuum system. This completed the process by allowing the glue to flow, impregnate and seal the ply layers.

Rob Legg’s inquisitive mind had worked out by trial and error with home-made equipment what aircraft manufacturers already knew. He was granted a patent on his system, started taking orders, took on employees and continued sailing competitively.

OLYMPIC FINN

Paul Elvstrom in his moulded Borresen Finn at the Helsinki Olympics 1952.

When you consider the years of meticulous preparation and training by Olympic sailors competing in Tokyo, its interesting to look back at how things were done a bit differently in the 1950’s. Rob Legg competed in the Finn trials for the Helsinki Olympics and comments;

“The sailing elimination trials for the Helsinki games were held on courses between Brighton and St Kilda. A big problem was no one in Australia had ever seen a Finn class boat, let alone sailed one. The Olympic committee couldn’t find a suitable single handed class boat for the trials. Their solution was to borrow six clinker-built cadet dinghies from Brighton yacht club. They were taken over to Savages yard in Williamstown and the masts and chain plates were moved a foot further forward and headsail gear removed. They were nothing remotely like the Olympic Finn.

The cadet dinghies were a completely open boat with a bowsprit and a lug rigged mainsail. This was in contrast to a Finn which has an unsupported mast and sail shape dependent on main sheet tension. Those cadet dinghies were, and still are a great training boat for youngsters, but a poor substitute for a Finn. I felt sorry for the eventual winner of the series going into an entirely different boat and expected to be competitive at the Olympics”.

Peter Attrill from Tasmania represented Australia in the Finn at Helsinki coming 22nd out of 28 boats.

The Finn has survived 18 consecutive Olympic regattas since its introduction at Helsinki 1952. Sadly the Enoshima regatta Tokyo 2020 is a farewell to the Finn at the Olympics. The FiNN is out while the BMX, 49FX, RSX and TV broadcast FiXX are in. For a wrap of “uneven signals” between World Sailing and the IOC here’s a link to Helen Fretter in Yachting World.

A classic Fairy Finn sailing on the Hamble

Still the same boat. Spanish Finn sailor Joan Cardona. Bronze medal Tokyo 2020

MOULDCRAFT

By the early 1950’s and after five years at Somerville, Rob Legg found a partner and built a factory in Frankston. Th business quickly expanded, making ply hulls for outboard runabouts, cabin cruisers, dinghy yachts, surf boats and surf skis.

Mouldcraft surf ski at Edithvale Beach Melbourne circa 1960.

Mouldcraft were invited to tender to build Finns for the 1956 Melbourne Olympics. RL recounts old school Olympic Committee and sports administrator shenanigans, that seem unchanged today;

“after going to a lot of trouble with our costings and being the only builders in moulded ply construction, we were confident of winning the contract. It did seem strange that the winning tender was just five pounds less per boat than ours and J Savage & Sons had never attempted to build a boat in moulded ply. Even stranger was, in the following week, we had a phone call from a member of the selection committee requesting we help by advising the winning tenderer on how to go about moulding the boats. I did not reply. We had more work than we could handle.

We were busy building Flying Dutchman, 5o5’s, Flying Fifteens, Jollyboats, Port Phillip 12’s, Kitty Cats and Moths”.

Mouldcraft didn’t win the Finn tender but Borresens in Denmark did in 1952

.

Like Fairy Marine, Mouldcraft in Melbourne were riding the dinghy wave, building local and international boats under license. Rob Legg’s business really exemplifies the post war dinghy revolution based on simple construction with ply and laminate. His 1950’s recollections sum this up;

In the last six years more progress has been made in boating than in the previous hundred. Fico and Ronstan had revolutionised the manufacture of fittings using stainless steel, sails were now being made in synthetics, wire rigging had gone from hand spliced galvanised wire to swaged stainless, spars were now mainly aluminium, the new synthetic ropes were a joy to handle and boats were half the weight of those built ten years previously”.

OZ GOOSE

Ply chine experiments are still going on today with a 12 foot box claiming 12 knots when planing.

12ft box Oz Goose.

Oz Goose shows off its planing hull and lug sail.

Credits: www.rlyachts.net