Sandefjord- a lucky ship

In March last year we published a short article entitled “Everybody loves the sixties, especially those who weren’t there”, about the circumnavigation of the Sandefjord. Well, this week we were lucky enough to receive a story on the same subject from Graham Cox, who actually WAS there!

Sailng through Great Barrier Reef waters, early August 1966.

By Graham Cox

On a bitterly-cold, midwinter day in early June 1966, the 46’, 50-ton, gaff-rigged ketch, Sandefjord, built in Risör, Norway, in 1913, and registered in Durban, South Africa, limped into Sydney Harbour with a broken mizzen mast lashed to the deck, 50 days out of Bora Bora in French Polynesia. The crew of five young men were not only shivering, but they were hungry, as all that was left of their provisions were a few cans of baked beans.

They were also exhausted. Instead of the expected SE tradewinds after leaving French Polynesia, Sandefjord had battled a series of SW gales, requiring the old ship to beat to windward for weeks on end, which had strained the seams, forcing the crew to spend endless hours manning the pumps, in between wrestling with the ship’s heavy, wet, canvas sails.

Storm off Sydney, 31 May 1966.

The final blow came in a storm while running down the NSW coast to Sydney, when an accidental gybe resulted in the mizzen mast breaking off just above deck level in the middle of the night. As Barry Cullen said afterwards, it was a miracle that nobody was lost overboard that night, as the entire crew battled to lower the spar safely to the deck and lash it in place.

Sydney offered a welcome respite. In Rushcutters Bay, the mizzen mast was repaired and re-stepped, the ship slipped, re-caulked and antifouled, with the willing assistance of a gang of admirers. Several weeks later, Sandefjord sailed merrily on its way, after a series of boisterous parties that were still being talked about when I arrived in Rushcutters Bay from Durban in 1972.

On the slipway, Rushcutters Bay, Sydney, July 1966

Sandefjord was already a legendary boat. It was the 28th rescue vessel built for the Norwegian Lifeboat Institution, designed by Colin Archer, and served in that capacity for 22 years, during which time three vessels with seven people aboard were saved from sure death, and 258 vessels with 1100 people aboard were rendered assistance, without which many of them may not have survived.

Sandefjord was bought out of service in 1935 by Norwegian yachtsman, Erling Tambs, who was already famous internationally for his 1928 voyage to New Zealand on a smaller Colin Archer double-ender, Teddy, with his wife, young son, and a dog called Spare Provisions, and for his book, The Cruise of the Teddy, in which it was plainly evident that Spare Provisions was at no time in danger of finding himself on the menu! They loved him without reservation.

After winning the inaugural Trans-Tasman Race from Auckland to Sydney in 1931, Teddy was unfortunately wrecked in New Zealand waters. After purchasing Sandefjord in Norway, Tambs set out for New York, to compete in a proposed transatlantic race back to Europe. SE of Bermuda, the ship was overtaken by what was almost certainly an early-season hurricane. In those days, there was no long-range forecasting, and little was known of these storms unless they came ashore, or were reported post-event by passing ships. Sandefjord ran off before the storm under bare poles, but was eventually overwhelmed by the sea, pitchpoling, with the loss of one man, the mizzen mast, and a plank out of the topsides. Having almost been pitchpoled myself, aboard the 60’, 32-ton, gaff-rigged schooner, Ishmael, in the Southern Ocean in 1980, I can imagine the scenario.

Ishmael was driven down the face of an unbelievably steep sea, almost twice the height of the surrounding waves, which were big enough to make you quake in your boots. I was on the helm, and lost my footing due to the steepness of the deck, as we careened down the wave, only saving myself from falling forward by clinging to the wheel. Our 22’-long bowsprit (including jibboom), buried itself into the trough, along with the entire foredeck up to the foremast, before the ship’s reserve buoyancy asserted itself and thrust Ishmael back to the surface, putting the vessel on it’s beam ends while doing so. Looking at Sandefjord’s bluff bows makes me realise that the sea which overwhelmed the ship must have been incomparably higher and steeper than the +/- 50’ monster that struck Ishmael.

When Tambs arrived in New York, he learned that the race he had come for had been cancelled. Undeterred, he then sailed Sandefjord back across the Atlantic, and on to Cape Town in 1939, via Tristan de Cunha in the Southern Ocean. He would undoubtedly have gone on to greater adventures if World War Two had not intervened. Sandefjord then spent many years in Cape Town. Bernard Moitessier, aboard Marie Therese II, saw the ship there in 1955, and called Sandefjord ‘a great big bull of a boat’.

By this time, neglect was taking its toll, and in the early 1960s, Sandefjord had been semi-abandoned in Durban Harbour, lying half-sunk at an outer mooring, where it would have remained had not two young dreamers, Barry and Patrick Cullen, not come along, bought it for next to nothing, then spent two years rebuilding the ship.

Relaunching day in Durban, 20 Oct 1964.

This was followed by a faultless, two-year, tradewind circumnavigation between 1965-6. Their mother mortgaged her house to finance the rebuild of the boat and the film they made, Sandefjord around the World, which was released in 1968 to great acclaim in South Africa, and eventually elsewhere. Enthralled, I went to see it at least twice a week for six months. There is no limit to passion when you are 16! The narration appears a little dated today, and some feel that the film would benefit from being edited, but I must have watched this film thirty or more times now, and still lap up every minute of it. It could never be too long for me.

Of course, Sandefjord holds a special place in my heart. It was the first yacht, if you can call Sandefjord a yacht, that I laid eyes upon as a 14-year-old in Durban in 1966. Until a local newspaper ran a two-page special feature about Sandefjord’s circumnavigation, after the ship returned to Durban, I had never even heard of people living aboard yachts and sailing the world. My dream was to be a professional ballet dancer, but some idle curiosity took me down to the yacht basin the next Saturday, which was near my usual weekend haunt, the Durban Central Library, to have a look.

While doing so, I was approached by a man from a catamaran, Rehu Moana, which was moored alongside Sandefjord. Introducing himself as David Lewis (the name meant nothing to me), he asked me to help him carry a box down from the yacht club. That led to a lifelong friendship with David, who profoundly influenced my life, though it was not until the following year, when 18-year-old Robin Lee Graham sailed into Durban aboard his 24’ sloop, Dove, that something clicked in my brain, and I decided that ocean cruising was what I wanted to do for the rest of my life. By then, I’d worked out I was never going to get into ballet school. Just the merest hint of the idea was enough to make my father’s face go purple…

After Sandefjord’s circumnavigation, the boat lay in Durban for a few years while the Cullen brothers finished editing their film and promoting it, but in 1971, Patrick Cullen, accompanied this time by his wife and children, sailed the boat in the inaugural Cape to Rio yacht race, before going on to the Caribbean and eventually the east coast of the USA. He made another film of that voyage, but I have never been able to locate a copy.

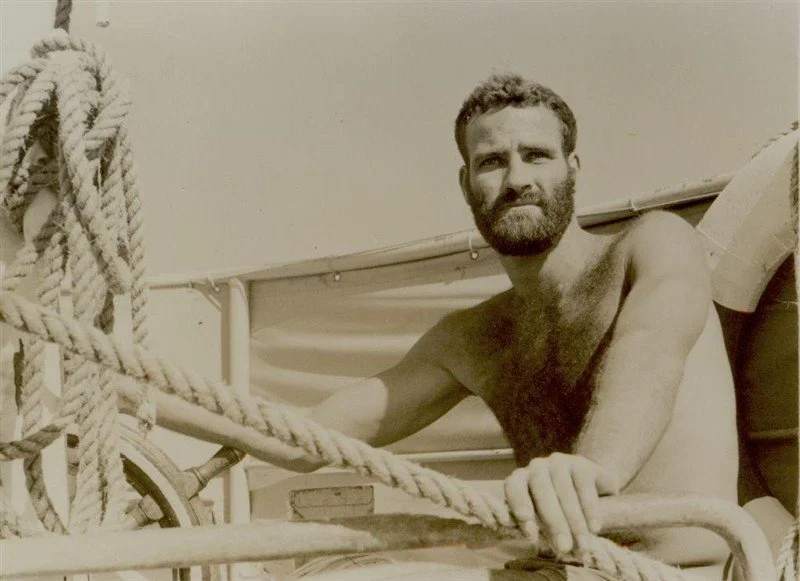

Patrick Cullen April 1965.

The thing about old, iron-fastened, softwood timber boats like this, built in cold climates, is that once you take them into warmer waters it becomes an endless struggle to maintain them. Patrick found it a losing battle, and the poor ship was starting to deteriorate again rapidly. But Sandefjord has always been a lucky ship, and once again a saviour appeared, in the form of a Norwegian sailor, Gunn von Trepka, who sailed the ailing vessel back to Norway, where it has undergone an extensive rebuild, taking it back to its original form, with bulwarks and oiled spars.

For many years, Gunn sailed the boat with her partner, taking young people to sea, but the ship is now maintained by the Colin Archer Society. Sandefjord will always hold a special place in my imagination, and has profoundly influenced my aesthetic and practical approach to cruising under sail.

Graham Cox. Author of the two-volume sailing memoir, Last Days of the Slocum Era.